digital texts: a return to aspects of an oral tradition?

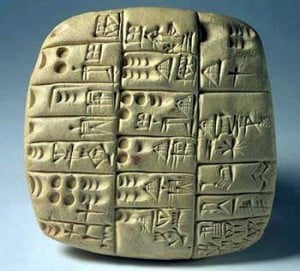

Ebooks are the latest stage of a process that began with the invention of writing. The ability to write thoughts and stories down allowed their distribution across space and time: a storyteller no longer needed to be present for his message to be communicated. These advantages are obvious, but there is also a profound disadvantage: that a text is a fossil of the author’s message, and that, disconnected from its living source, it can no longer adapt.

The printing press made it possible to clone texts that were free from the errors of manual copying, and allowed vastly more examples of a text to exist, thus facilitating wider distribution. The digital text has made it easy to clone a text, and the internet has facilitated the speed and extent of their distribution. Living as we do in a period of transition from paper to digital texts, many of us have qualms about what we may be losing. There is the issue of aesthetics that I address in this post, and there is also an anxiety that comes from the loss of there being a definitive version of a given text.

A digital text compared to that text printed on paper is like a vessel of clay before and after it has been fired; an essential quality of a digital text (of any digital object) is that it remains for ever malleable. This malleability robs us of an important benefit that is conferred by a printing press: that it produces identical and ‘fixed’ versions of a text. It is this aspect of a printed text that has compelled the author to strive for a perfect version of his text; for once it is printed it will have whatever failings he has given it. Apart from the changes that he can make in a new edition – nothing can be added, nothing taken away. That a text cannot be modified once it has been printed has also drawn to the process an entire machinery of publishing: editing to make sure the structure of the text is sound; copyediting to remove any errors. The capital outlay invested in printing a text (at least until recently) further increased the need for a publisher. A natural partnership existed between an author and his publisher because they had a common interest: that the text be as complete as possible.

That a digital text remains malleable after publication, weakens the necessity for this partnership (as instant distribution of digital texts, and the lack of need of capital to print large numbers of texts that then require warehousing, weakens it further). Many authors will still wish that their texts be professionally edited and copyedited – however there is a new option: that this can now occur after the text is published. It is even possible that the readers of the text could be brought in to correct any errors. (I deal with the notion of direct reader correction of digital texts in this post.) On balance, I feel it is likely that an author would wish to retain control of his text. However, he could elect to use some kind of ‘crowd sourcing’ not only to have his text corrected, but perhaps even edited (I discuss my reservations about this latter notion in this post). The limited iterations of a printed text that new editions provide to an author, become limitless with a digital text. An author could choose to change and evolve his text in much the same way that software is now being constantly updated on our computers. Further, whereas some authors have had printed texts supplied with different covers for different markets (and types of readers), the author of a digital text could target any number of different markets with different versions of his text: abridged, simplified, with different endings etc. So, though we may lose the ‘definitive text’ we gain all kinds of other compensations.

There is, it seems to me, a profound consequence to all this. For all the advantages conferred by the invention of writing on the creations of an author, one thing was lost: the ability that the author had to keep his work ‘alive’. When all stories, all arguments, all knowledge had to be conveyed through speech, the only permanence of these lay in the memory of those who had heard them spoken. An oral storyteller could respond to his audience as he was telling them his stories. The next time he told those stories, he could improve them from his experience of how they were received at the previous telling. I am left wondering if, with the advent of digital texts, we have, in a way, come full circle. While still benefitting from most of the advantages conferred by several thousand years of development, every author can also have back something of what was lost from the oral past. Indeed, it may come to be seen that the period during which fixed texts held sway was merely a temporary aberration.