Lobsang Rampa and what we choose to believe

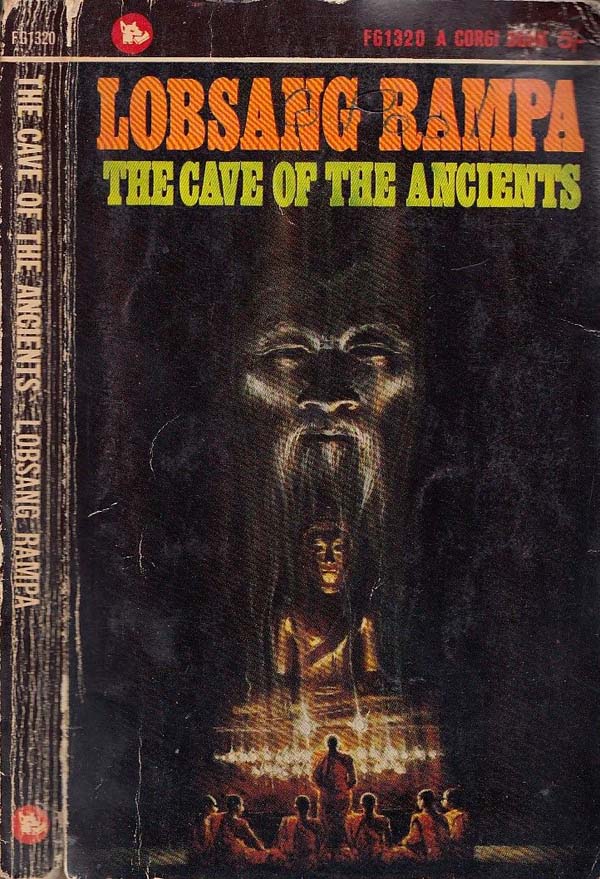

When I was perhaps 14, I was intrigued with books by Lobsang Rampa, but I could only afford to buy very few books with my pocket money, and so I would buy another Asimov.

Leafing through one of those Lobsang Rampa books, I recall reading about the mummified bodies of giants hidden under the Potala Palace in Lhasa. I don’t know whether I knew anything much about Tibet then, or whether, indeed, it was this that kindled my interest. Certainly, throughout my life, an abiding fascination for Tibet has lurked in the back of my mind. It was invoked in Ayesha: the Return of She, H. Rider Haggard’s sequel to She—though I read that much later. It haunted me with visions of Shangri-La; though I only read Lost Horizon by James Hilton (another bestseller fantasy about Tibet) relatively recently, and watched (or re-watched? how else did I know about it?) the 1937 film by Frank Capra. Even as the Dalai Lama became an accessible celebrity, those giants under the Potala lurked in my unconscious; I still hold on to a notion of a Tibet that is inaccessible and hidden from the world—even though the Chinese have built a railway to Lhasa, and Tibet is exposed to the outside world, so that it would seem there is no longer anywhere for any of these sorts of mysteries to hide.

So, today, I was watching a spurious, though entertaining—fascinating, even—YouTube documentary about ‘Hollow Earth’ theories. None of it made much sense, but the narration was so earnest, and the ideas—bonkers as they are—so fascinating, and then Lobsang Rampa was mentioned, bringing him back into my mind, more than 40 years on, and I decided to look him up on wikipedia.

And what did I discover but that Lobsang Rampa was actually a Cyril Hoskin, a school dropout born in Devon, the son of a village plumber. This was the man who had written these books. When unmasked by a private detective (yes, really!), Hoskin claimed that his body was now occupied by the spirit of a Tibetan lama—Lobsang Rampa.

Hoskin’s books were bestsellers, and many people who went on to become academic Tibetologists and buddhologists said that “it was a fascination with the world Rampa described that had led them to become professional scholars of Tibet”. The same professor who discovered this added that, when he gave The Third Eye (Hoskin’s most famous book) to a class of his at the University of Michigan, without telling them about its provenance, the students were “unanimous in their praise of the book and, despite six prior weeks of lectures and readings on Tibetan history and religion, they found it entirely credible and compelling; judging it more realistic than anything they had previously read about Tibet.”

So, it seems that I was not the only one who had his views of Tibet formed by Mr Hoskin.

Even the Dalai Lama has apparently admitted that, although Hoskin’s books were fictitious, they had created good publicity for Tibet.

All of this seems to me to point to a rather interesting—alarming, even—characteristic of human beings: we believe that which we want to believe. In this case, many of us have become captivated—have fallen victim to—a mirage of Tibet that we cling to so tightly, that when a plumber from Devon spins fantasies of the place, they become bestsellers and reinforce, in the minds of many people, a collective hallucination of that land so appealing, that it eclipses its reality.

Beyond this, my other examples seem to have a common theme: things being interpreted through a white perspective. Hoskin, a white man, masquerading as a Tibetan Lama. Ayesha, a white woman, lording it over savages in Africa and then Tibet. In Shangri-La, white people stumble into a mysterious valley hidden somewhere in the Himalayas. Though this valley is ruled by lamas, it turns out that their head is a white Frenchman, who also masquerades as a Tibetan.

I am reminded of an interview I watched recently with the boxer Muhammad Ali, in which he riffed on how, growing up, everything white was good, everything black was bad. He pointed out something that, to me growing up seemed perfectly natural, Tarzan, a white man in Africa, was the one who understood the animals and could communicate with them, when the black men all around him could not.

All this could be seen as colonialism, racism even. More innocently, we could see this as just white people doing what people everywhere else do: interpreting the ‘exotic other’ through their own cultural forms and experiences. I grew up on this sort of storytelling—it illuminated my childhood and fed the growth of my imagination—how can I regret that? Even the Dalai Lama—with his characteristic grace—apparently said that Lobsang Rampa/Hoskin had benefited Tibet.

This said, now that we are all growing up from this sort of ‘innocence’, it is time to set aside this sort of white self-obsession, to put aside these distorting fantasies, to make an effort to see everyone in the world as they really are.